How to Practice Speaking a Language Alone

You've been working on your Spanish for months, maybe years. You can read news articles without reaching for the dictionary every sentence. You understand most of what you hear in podcasts or shows. Your grammar is solid, at least on paper.

But when it comes time to actually speak? The words you know so well when reading suddenly vanish. Your brain scrambles. You stumble over basic phrases you've seen a thousand times. And the thought of speaking out loud when no one else is around feels... awkward.

If that sounds familiar, you're not alone. And more importantly, you're not stuck.

The Speaking Problem Most Learners Face

Reading and listening are passive skills. You recognize patterns, absorb meaning, and build knowledge. But speaking is different. Speaking requires you to retrieve words and grammar structures in real time, organize them coherently, and produce them out loud, all while your brain is also trying to monitor what you're saying.

It's cognitively demanding. And if you've spent most of your study time on input: reading articles and books, listening to podcasts, watching TV; you haven't trained your brain to do the harder work of active production.

This is why so many intermediate learners hit a wall. They know enough to understand, but not enough to speak with confidence. The gap isn't knowledge. It's producing language under pressure.

Why Speaking Alone Actually Works

There's a common myth that speaking practice only counts if someone else is listening. That you need a tutor, a language partner, or at least a sympathetic friend to practice with.

But research on retrieval practice tells a different story. When you actively try to produce language, even when you're alone, you're forcing your brain to retrieve vocabulary and grammar from memory. This retrieval process is what strengthens learning. In fact, studies on the testing effect show that attempting to generate language produces significantly better long-term retention than passively reviewing the same material.

Put simply: trying to say something, even when you get it wrong, teaches your brain more than reading the correct answer again. If you're interested in more information about the research in this area, we recommend Make it Stick (Brown, Roediger, McDaniel).

Solo speaking practice works because it gives you unlimited reps. You can practice the same structure five times in a row without boring a conversation partner. You can fail, restart, and try again without embarrassment. And you can focus entirely on the specific grammar or vocabulary you're trying to master, rather than navigating the unpredictability of real conversation.

What Makes Speaking Practice Effective

Not all speaking practice is equal. Talking into the void without structure or feedback doesn't build fluency, it just reinforces whatever errors you're already making.

Effective speaking practice has three elements:

Clear prompts tied to specific structures. You need to know what you're practicing. "Talk about your day" is too vague. "Describe three things you would do this weekend using the conditional tense" is concrete. You know what success looks like.

Active production, not recitation. Memorizing and repeating scripted phrases doesn't train your brain to think in the language. You need prompts that require you to construct original sentences on the spot, pulling from what you know and organizing it in real time.

Immediate, explicit feedback. Here's where solo practice usually falls apart. If you speak into a recording app or talk to yourself in the mirror, you have no way of knowing what you got wrong or why. And research on corrective feedback is unambiguous: explicit correction, where you see exactly what was wrong and understand the rule behind it, produces substantially better learning outcomes than vague or absent feedback.

A 2010 meta-analysis by Shawn Li found that explicit corrective feedback had medium-to-large effects on second language acquisition, with effect sizes around d=0.64. In practical terms, that means learners who receive clear explanations of their errors improve significantly faster than those who don't.

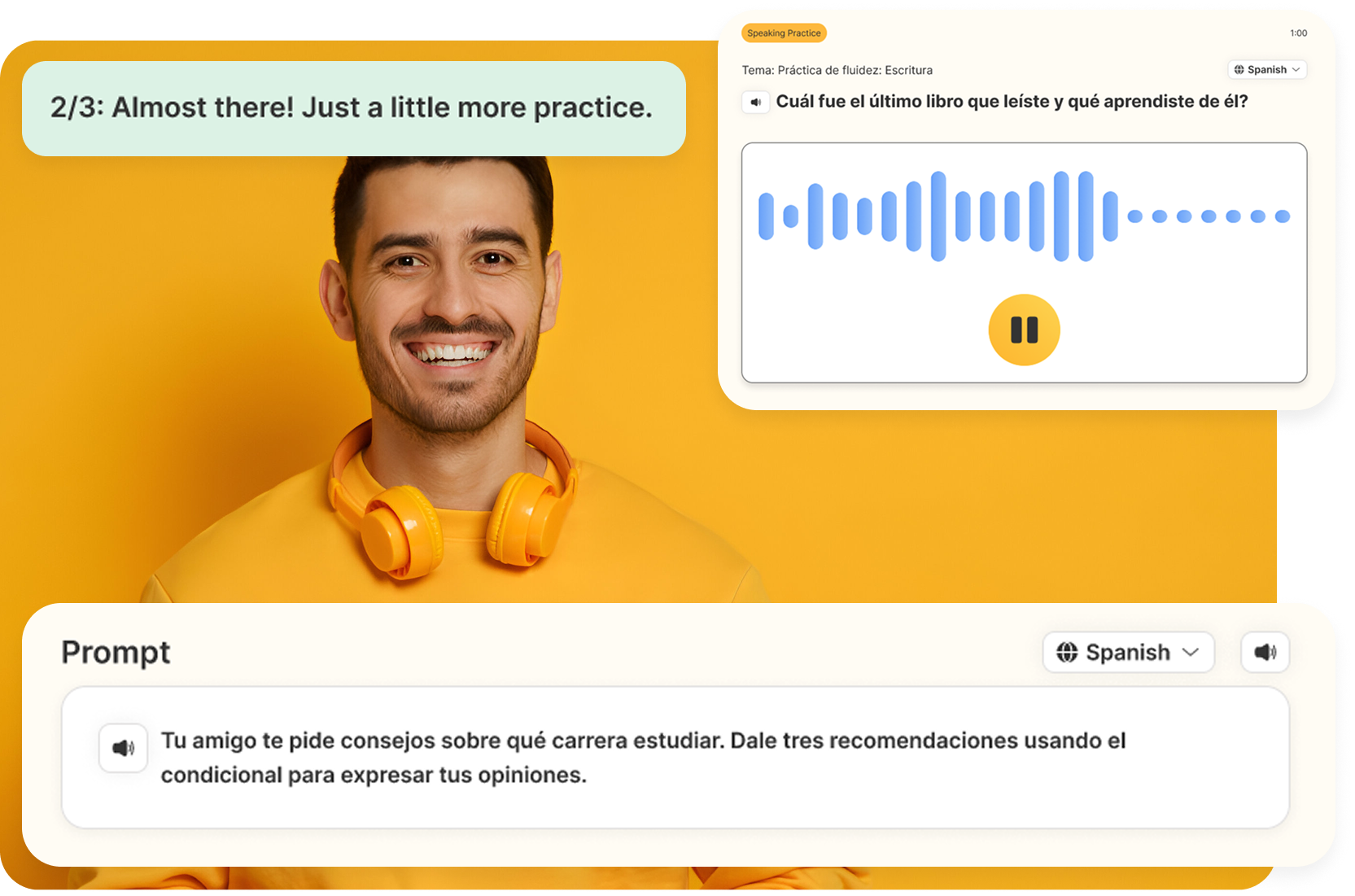

How Dioma Structures Speaking Practice

Dioma was inspired by this research. Our speaking exercises give you structured prompts tied to CEFR-aligned grammar topics like conditional tenses, subjunctive mood, prepositions of time, so you always know what you're working on.

You record your response at your own pace. No one is waiting on the other end of a video call. No pressure to perform perfectly on the first try. You can pause, think, and restart if needed.

Then you receive feedback. Not generic AI cheerleading, but targeted corrections based on an expert-written curriculum. If you used the wrong tense or missed a key structure, Dioma shows you exactly what was incorrect, explains the rule, and offers additional practice if you need it.

The system also tracks which structures you're struggling with and adjusts future prompts accordingly. If you consistently make mistakes with ser vs. estar, you'll see more exercises focused on that distinction until you internalize it.

This is where solo practice becomes genuinely useful. You're not just speaking into the void, you're getting the same kind of corrective feedback you'd get from a skilled tutor, but on your schedule and at a fraction of the cost.

The Generation Effect: Why Mistakes Help You Learn

One of the most counterintuitive findings from cognitive science is that making errors during practice actually improves learning, as long as you receive correction afterward.

This is called the generation effect. When you attempt to produce language before being shown the correct form, your brain works harder. Even if you get it wrong, that effort creates stronger memory traces than passively studying the right answer would.

The key is that the error can't go uncorrected. If you make the same mistake repeatedly without feedback, you're just reinforcing the wrong pattern, which can lead to fossilization. But when you attempt, fail, and then see exactly why you failed, your brain encodes the correction more deeply.

This is why Dioma's speaking exercises start with the prompt, not the model answer. You try. You make mistakes. Then you see what you got wrong and why. Each cycle of attempt → feedback → retry moves you closer to fluency.

Confidence Comes From Doing, Not Knowing

Most intermediate learners already know more than they think they do. The problem isn't that you need more grammar explanations or vocabulary lists. The problem is that your passive knowledge hasn't been activated through production.

Confidence doesn't come from knowing the conditional tense exists. It comes from using it successfully enough times that it feels automatic.

Dioma's speaking practice is designed to give you those reps. Whether you're preparing for the DELE, planning a trip to Madrid, or just tired of freezing up when you try to speak, structured solo practice helps you turn knowledge into ability.

You can practice in 15-minute sessions whenever you have time. You don't need to schedule anything with anyone. And every session moves you forward, because every attempt, even the ones that need correction, is teaching your brain something new.

You Don't Need to Be Fluent to Start Speaking

The biggest barrier to speaking isn't lack of knowledge. It's the belief that you're not ready yet. That you need to study more, review more, know more before you're allowed to practice speaking.

But that's backward. Speaking is how you become ready.

Dioma gives you a structured, low-stakes way to practice speaking on your own terms. No embarrassment. No judgment. Just you, a clear prompt, and immediate feedback that helps you improve.

Dioma is built for learners who've outgrown the basics. Structured curriculum, smart feedback, real progress. Try it free for 7 days.